In a world increasingly defined by visibility, authenticity and performance are becoming harder to tell apart. Behaviors once rooted in personal preference now seem shaped by how well they can be presented—and rewarded—online.

We don’t just do things anymore. We broadcast them.

Much of modern life feels like it’s lived on a public stage. Social platforms have made attention a form of currency. If something photographs well, signals taste, or aligns with a cultural aesthetic—it spreads.

Individual choices begin to reflect trends, not personal desire. Enter the age of performative consumption.

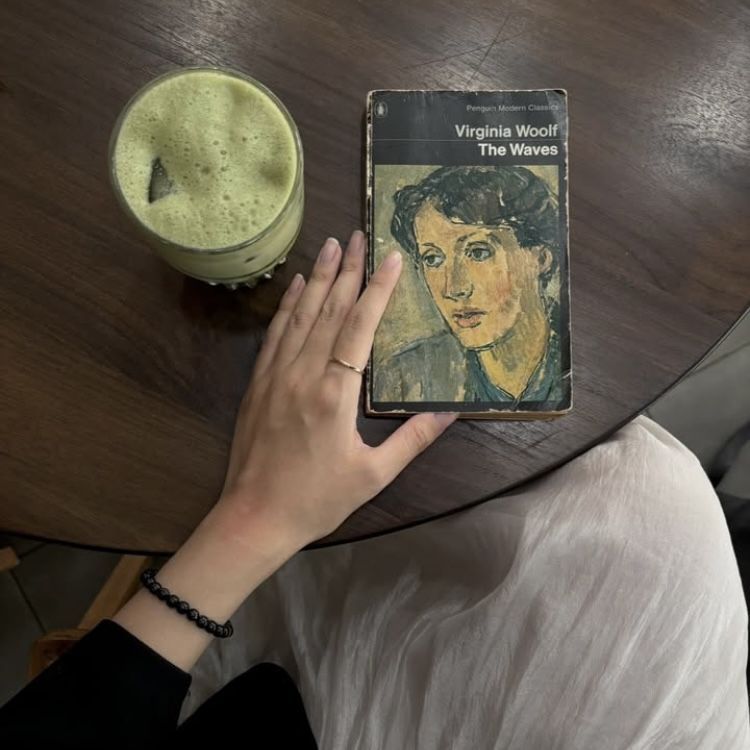

Take matcha.

It’s everywhere:

- Morning matcha lattes in soft green gradients

- “Health glow” TikTok routines

- Matcha powder arranged neatly beside skincare serums

Do people genuinely enjoy it? Many do.

But there’s also a growing number who tolerate its bitter, grassy flavor because it looks like wellness. It signals discipline, minimalism, and a soft, elevated lifestyle. A cup of coffee may feel too ordinary — but matcha captures an entire identity in one sip.

A lifestyle becomes a brand.

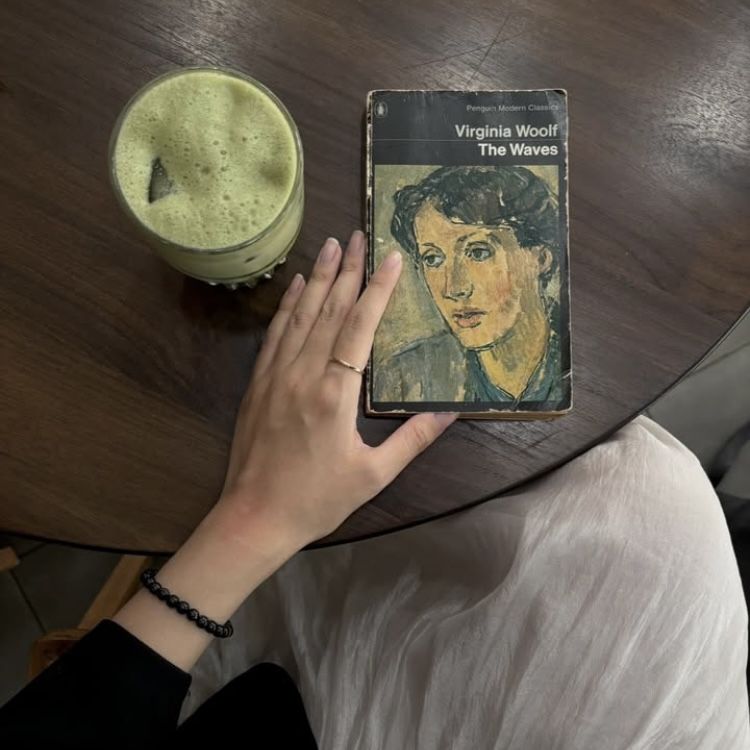

Similarly, classic literature has become a social marker, especially online. Videos and photos show shelves stacked with Pride and Prejudice, The Picture of Dorian Gray, or The Odyssey—pristine, untouched, and perfectly color-coordinated.

There’s nothing wrong with loving the classics—they’re classics for a reason. But many people collect them not for reading but for signaling:

- intellectualism

- cultural sophistication

- “dark academia” vibes

Owning Hemingway becomes shorthand for depth.

Finishing a 700-page novel becomes proof of discipline.

We curate identities through objects we rarely engage with.

This logic extends beyond aesthetics. Even kindness, activism, and empathy can be shaped by what is seen. A donation may not “count” until it’s shared. Supporting a cause becomes entwined with public affirmation—making the act both real and staged.

When virtue is measured by visibility, silence can feel like failure.

The aesthetics that signify “good taste”—matcha over instant coffee, vinyl over streaming, classics over paperbacks—often require money, time, and cultural literacy that not everyone has access to. The performance of taste becomes a quiet gatekeeper. Those who cannot participate are viewed as lesser, “uncultured,” or behind the trend.

The message becomes clear:

Only some people can afford to look authentic.

Elitism hides behind soft filters and curated feeds. Objects meant for enjoyment become symbols of belonging, and exclusion becomes disguised as aesthetics. Online culture rewards not just visibility, but a specific kind that aligns with middle- and upper-class ideals.

In this performative landscape, the inner self can feel underdeveloped compared to the persona crafted for others. We become fluent in aesthetic interests—matcha, vinyl records, annotated classics—while struggling to articulate the preferences that genuinely move us.

The fear of being uninteresting pressures us to adopt interests that are visually or socially validated.

Being witnessed becomes more important than being sincere.

We can’t step backward into a pre-digital age—nor should we. These trends aren’t inherently negative. People do discover joy in the things they originally adopted for the aesthetic.

But balance matters.

There’s value in:

- Trying something without posting it

- Reading books we genuinely enjoy, even if they’re not “literary”

- Drinking what tastes good, not what photographs well

- Enjoying our lives offline and unobserved

Joy does not need an audience to exist.

“When image becomes identity, the truest parts of ourselves are the ones left unseen.”

Perhaps the question isn’t whether we’re more performative—we are.

The real question is whether we can recognize when we’re performing… and choose, sometimes, not to.

Leave a comment